"May you live in interesting times." --a reputed Chinese curse, which probably isn't real

Years ago, I decided to write a story about a person with the most common first and last name, an "everyman", set in part historical fiction, part fantasy/sci-fi, part philosophical novel. Another influence is classic novel

Journey to the West (西游记

Xī Yóu Jì).

A short summary of the story follows.

Sometime during the Tang Dynasty in China (618-907), in the old capital of Chang'an (now called Xi'an), a man named Lee (李, Lǐ, meaning "plum") was born. He lived an unremarkable but virtuous life as a civil servant, husband and father.

For many years, he had an envious rival who hated him for some reason. He secretly sought dark magical powers with the plan of ruining Lee. He would eventually succeed.

When Lee was forty years old, his rival, named Wang (王 Wáng, "king"), put a curse on Lee. It was an ironic curse: he would be unable to die, either by disease, old age or violence, and never rest in peace. He would also gain knowledge of all things, but also suffer profound sadness and despair because of it. He would wander the world, forced to witness history in all its brutality.

Wang also murdered Lee's wife and children, and set it up so that Lee had committed the crime himself. Lee would be forced to flee China and wander in the Gobi for centuries. Not long after the incident, in 907, the Tang Dynasty fell and China was divided.

Sometime around the year 1200, a few years before Genghis Khan began to build his vast empire, Lee had a dream of a great ruler of a far away nation. It was Harun al-Rashid, the Abbasid caliph. He was told that he would need to go to Baghdad and settle there.

He would gain even greater wisdom through his studies at the House of Wisdom, living in a peaceful and prosperous city. That all ended in 1258, as Hulagu Khan and his forces destroyed the library and sacked the city. Before then, Lee, who had been following Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, became a Muslim and took the name Muhammad. He would fight, to no avail, in defense of his adopted home city.

(I chose the name because either Lee or Wang is the most common surname in the world, and Muhammad is the most common given name.)

After the conquest of Iraq, Lee fled to the city of Konya and Anatolia (now Turkey) and met a poet and mystic named Jalal al-Din Rumi. The two became friends and traveled together, once to Damascus, and Lee learned the teachings of Sufism. He believed that the Three Teachings he followed before, and the monotheistic faith of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, were all facets of the same truth, seeing all as one as God is one. He also learned, through another dream, that he would be allowed to rest in peace, but not until after the second coming of Christ, whom he would meet along with the Mahdi.

He remained with Rumi in the Mevlevi community until his death in 1273. Lee would continue his travels through Asia along the Silk Road. One day, in modern-day Kazakhstan, he met a man from Venice, another adventurer, named Marco Polo. They traveled together for a time, sharing what they learned. He also may have fought in the Crusades, though he hated war; he had witnessed enough already.

In the 14th century, he witnessed the rise of a new empire: that of the Seljuk Turks. A new empire, of the Ottomans, replaced the Seljuks, and in 1453, Constantiople was conquered. Lee would soon settle in the city now known as Istanbul.

In 1536, the Turks became allies with another great nation to the west: France. Lee would travel through Europe. He witnessed wars with other states, and the invasions of Vienna. He witnessed the rise of the West, and the revoltuions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

He learned of a young and distant nation: America. He was told in another dream that he was to go there. After traveling to India and Southeast Asia, he crossed the Pacific and settled in San Francisco in 1849. It was the beginning of the Gold Rush. He witnessed the greed and decadence associated with it. Meanwhile, he worked and lived among the laborers on the Transcontinental Railroad. (He was still physically forty years old.)

During his life in the United States, California became a state in 1850, the Civil War was fought and won by the Union, and vast industrial and technological advances were made.

He had renounced war, but would support the effort against the Japanese after learning what was done to Nanjing in 1937-38. After bearing decades of anti-Chinese discrimination, he finally became an American citizen soon in 1945, a few months after the end of World War II.

Also during his time in America, he fell in love for the first time after losing his wife over a thousand years before. They never married, however. He kept his curse a secret from all, including his beloved.

Though he would continue to work and travel throughout the world, it would be years before he would finally return to China in the early 21st century, when his company sent him to Beijing. He learned that his old rival Wang had also become immortal, and a very powerful wizard (a necromancer), who had planned on conquering China and the world. He was soon to face his enemy.

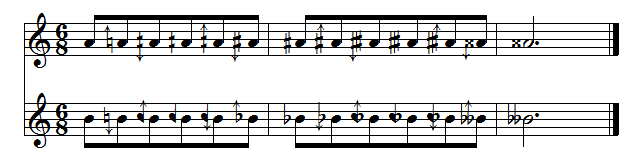

(Lee also wrote a diary, in many volumes, in his own language: a mixture of languages, mostly of Middle Chinese and Arabic.)