The music and writings of Danny Wier, a composer/musician based in Austin, Texas who dabbles in philosophy, history, politics and everything else.

28 December 2014

Doktoro Esperanto--an opera

The libretto, of course, would be in Esperanto, though there may be lines in Yiddish, Polish and Russian. (I may let someone else write the libretto.)

I would be using 72 equal temperament, of course. I do plan on finishing my Second Symphony first, though.

27 December 2014

"Virtual pitches" on timpani rolls

At the other extreme is infrasound. Anything below 20 Hz is more likely felt, not heard. (That applies to the fundamental, not harmonics.) Few acoustic musical instruments can play pitches that low--the first is E flat octave 0, at 19.45 Hz. 32-foot organ stops can play in that range. The low C is 16.35 Hz in standard tuning.

The Sydney Town Hall Grand Organ has a 64-foot stop, so it can play pitches in the negative-first octave, the low C being 8.18 Hz. With audible overtones, pitches this low are heard as beats rather than tones, and have been described as sounding like timpani rolls.

Which led me to another experiment...

This might require some considerable skill by percussionists, and certainly a metronome. If a roll on timpani, or bass or snare drum, could be an exact number of strokes per second, it would simulate an extremely low pitch. A double-stroke roll at 16.35 Hz would be a similated C0, which would go well with a timpano tuned to concert C2 (65.41 Hz). The drum should be tuned an octave, two octaves or a perfect twelfth above the virtual pitch.

So far, I have timpani rolls with specified frequencies in two movements of my Second Symphony: XXXVI. Montana and XXXIX. Nebraska.

Also, if an organ is being used, one still can produce resultant tones, by playing parallel fifths to simulate lower registers. (In Symphony No. 1, ninth movement, I used a resultant B-2, or about 7.72 Hz.)

22 December 2014

Symphony No. 1: The Cipher, the Devil's Ball

This object, called the Cipher (from Arabic صفر şifr "zero; empty"; see cipher), may not even be real. It just exists somehow, but only as an illusion. It is a shadow in Plato's cave, but it is a shadow of nothing.

It is an object of pure lies and deception. It promises great magical powers and knowledge, and may grant such powers, but ultimately it steals power. It survives and grows on evil deeds, but usually thrives on ignorance and folly.

It seems to have fallen to Earth from space many thousands of years ago, in the form of a marble-like sphere of black glass, one centimeter in diameter. It often shines with multi-colored light which swirls around it, like a tiny black hole.

Its influence on the world was greatest around 10,000 BC, but after the collapse of the city-state of Hriya, which possessed it, it disappeared, only to turn up again around the year AD 2000. Many leaders of the world, political, business and religious, who learned of the object and its powers, began to seek it, but before any of them even found it, they were already corrupted.

18 December 2014

Why I like Ravel's Boléro

But he's stuck with Boléro, which was originally a ballet, but it's almost always presented as a straight-up symphonic poem.

Now why do I like this thing, with no changes in rhythm, little deviation from the key of C major, and that relentless snare drum?

First of all, it is one of the earliest examples of musical minimalism à la Reich, Riley and Glass, the way it was meant to be. A simple motif is repeated many times, but there are slight deviations as the piece progresses. In this case, it's mostly the dynamic, getting very gradually louder all the while. The two-part melody is reiterated using different instruments and instrument combinations. These timbre mixtures function like organ stops, and Ravel even has higher instruments play mutations, the quints and nazards a fifth higher.

Schoenberg and Webern used such timbral combinations in their work, and called this technique Klangfarbenmelodie. It effectively gives the composer more instruments than the individual woodwinds and brass allot.

Also, Ravel, along with the later Prokofiev, made the saxophones a legitimate part of the symphony orchestra. These are able to better be heard in a loud tutti section than oboes and bassoons, so I have double reeds double saxes, if they can competently play the latter instruments. I like to have altos and tenors double horn parts to cut through trumpets and trombones (e.g. "California", the finale of my Symphony No. 2), but they can make violas and cellos sound even more sensual ("Minnesota" from the same work).

Therefore, Boléro is a demonstration of the capabilities of the orchestra, which possibilities had not been explored before the modern era (beginning circa 1890).

By the way, it's cliché, but I've never... you know... to Boléro. I think Carmina Burana's better for a passionate tryst, because it's about an hour long, and the words themselves are erotic in nature.

16 December 2014

Symphony No. 1: Elven cosmology

All of existence dwells in a continuum of realms, where Paradise is at the top and Hell is at the bottom. The material world, traditionally called Earth, is in the exact middle. The ancient people of Ħrîya understood the solar system to be heliocentric, and the planets to possibly be locations of distant realms.

The continuum of realms (usually, five are listed, but the number may be as large as infinity) has much in common with the six realms in Buddhism, but bears obvious influence from the monotheistic faiths: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Difference include the union of the human and animal worlds into a middle material world (again "Earth"), and the existence of only one supreme Deity, who has no name, but could be called the Monad, the One or the Unity, which is Being itself.

In the five-realm system, the five realms are:

- Paradise, the perfect world as it was originally created until it was corrupted by the False Being, the Devil. This is a vast garden of worlds, as large or larger than the material universe, where there is no death, no sleep, no hunger, no sickness, no suffering and no strife. The center of this world is the gigantic temple of God, made of gold, silver and precious jewels that will never tarnish. It is eternal daytime because God shines like a sun above the world forever. The blessed here live in perfect bodies, forever young, with perfect lives in great mansions.

- Heaven, which is a celestial world, but not the same as Paradise. Here, the living creatures, often called djinn, are no longer bound by flesh, but exist as pure spirit. Because of the lack of material existence, they are free of attachments to worldly lusts, but do still contend with the ego, pride and envy of those who have attained perfection. Ego is the only thing that keeps them out of Paradise. However, it is still possible to have malice, and negatively influence the next lower world (and be cast out into a lower world).

- Earth, that is, the material world of this universe. This is a mixture of Paradise and Hell, good and evil, joy and sorrow. Living things become born and then die, there is sickness, suffering and strife. The way of escape is to become detached from material desires, do deeds of benevolence and avoid acts of malice. Those that do, can be reborn into a higher world, with God as judge. Those that fail, may find themselves as a lower world, with only the mercy of God to help them.

- Limbo, or Sheol, or the Grave. Those with excessive attachments to the world, but not an overabundance of intentional evil deeds, may end up here. This is a place of depravation, but not the punishment of Hell. It is a gray, dark and gloomy world where the dead weep, hunger and live with regret. The only light is a faint red glow in the sky, a sun obscured by dark clouds. Those that dwell here, described as ghosts and shambling corpses, can only wait for rebirth in Earth. There are three types: those bound by (sexual) lust, those by gluttony, and those by greed. However, their wantonness was not so great that they habitually caused harm to others.

- Hell, the place of evil demons. Only those who have done heinous deeds with full freedom of will and knowledge of the consequences of such actions, may go here, if at all. Fortunately, no one is sent here forever, because a non-eternal being cannot commit an eternal sin. There are six chambers of Hell, each ruled by a tyrannical archdemon:

- Red Hell: a place of fiery volcanic lands of hot stone, blazing caverns and choking black smoke. Here is where the murderous and violent are sent, and they are constantly at war with each other, refusing any friendship or love.

- Green Hell: a toxic swamp full of trees with tearing, poisonous thorns that cause great pain. Those who harmed people through envy, lies and slander go here.

- Yellow (or Gold) Hell: a ship of fools, sailing on a storm (or in midair through a storm), continuall struck by lightning. Inside are traps such as sharp blades and crushing walls. Those so given to lust, gluttony, greed and desire for power that they harmed others may be doomed to be trapped within.

- Blue Hell: a frozen land surrounded by high mountaints with sheer cliffs, that includes frozen lakes. A bitter cold wind blows constantly, and terrible flying beasts, called wyverns, tear and sting at its naked inhabitants, who committed sins of omission; their laziness and apathy caused harm to the innocent.

- White Hell: a strange world, in that to the eye, it appears to be Paradise. (This is the only world that isn't perpetually dark; there is only enough light in the first four to see the nature of punishment.) However, its inhabitants, sent here for fraud and deception, and also tyrants and evil sorcerers, live in constant despair and confusion, and are slaves to the demons who rule this place. There is a temple at the center, but it is a temple to Pandemonium.

- Black Hell: the worst of the Hells, an empty void, like the space far away from galaxies, where nothing exists. There is no light, no substance, no awareness. It is not certain who is sent here, but it is often believed that it is those who committed the worst acts of betrayal. Here dwells the ultimate evil, the thing that should not be, that only exists because of the evil and foolishness of souls, who also has no name, but is often called the Cipher (from Arabic صفر sifr, "empty", also the source of the word "zero").

15 December 2014

Why I'm doing all this

Since the 1990s, I have been disabled due to a severe mental illness (bipolar disorder, but I was once diagnosed with schizophrenia). I also have chronic fatigue and pain, caused by something that hasn't been diagnosed yet.

The last time I held a full-time job, it was in 1997, as a computer repairman in Lufkin, Texas. I was also homeless for a time and lived in my car. I can no longer drive now due to poor vision and reflexes, and also not being able to afford a car.

But I could afford an internet account, at least dialup. I didn't want to be completely idle, and I never got to get my college degree, so I spent hours every day educating myself on many things. Over the years, I've done things like teach myself a few languages, philosophy and music composition.

I also played bass in a few bands, but none of them ever went anywhere (I kept ending up with slackers who used band practices as excuses to drink and smoke pot). I gave that up, at least for now, and devoted myself to composing full-time. I also started looking for work on movies or games, and have written one score for an indie film so far.

I haven't been able to make much money as a composer yet, but I have met some fellow composers, and got invited to hear an arrangement I did of a friend's work--in Turkey. So now I want to travel the world, if I only had money.

The real reason I became a composer, however, is to give myself a raison d'être, to ward off the despair.

I was also married once, but that didn't work out well. We didn't have any children. I'd like to have another chance at marriage and family, but I never can meet anyone.

13 December 2014

72 equal temperament in old-school MIDI

I started out using basic 12-tone tuning, then experimented with quarter tones (for non-piano instruments, of course), then spent years trying to figure out what tuning system I wanted to use (I was stuck on 53-equal for a while).

Then, after discovering miracle temperament, and the wonders of 72 equal temperament, and the glaring fact that 12 × 6 = 72, I decided to go with that. With a typical orchestral work, using 16 or more channels (I can load multiple instances of ARIA Engine for Garritan if I need more), I insert in-line pitch bends when needed. It's not perfect, since the pitch bends do affect release and reverb, but it gets the job done, and I can play it all back the way I want it recorded.

Also, ARIA uses Scala tuning files for tuning individual pitches, e.g. if you want all Es, Bs and F-sharps to be 50 cents flat, or you want quarter-comma meantone or Werckmeister well-temperament, and so on.

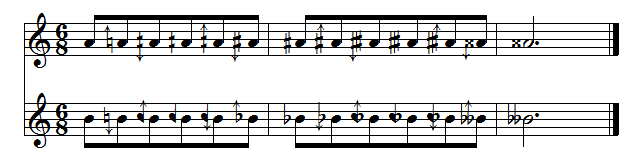

I haven't been entirely consistent on notation for 72 equal. If I want exact pitches specified, then I use a full system of regular accidentals, a de facto standard quarter tone notation, and arrows for morion (16.67 cent) adjustments:

The Legend of Muhammad Lee (Symphony No. 3)

"May you live in interesting times." --a reputed Chinese curse, which probably isn't realYears ago, I decided to write a story about a person with the most common first and last name, an "everyman", set in part historical fiction, part fantasy/sci-fi, part philosophical novel. Another influence is classic novel Journey to the West (西游记 Xī Yóu Jì).

A short summary of the story follows.

Sometime during the Tang Dynasty in China (618-907), in the old capital of Chang'an (now called Xi'an), a man named Lee (李, Lǐ, meaning "plum") was born. He lived an unremarkable but virtuous life as a civil servant, husband and father.

For many years, he had an envious rival who hated him for some reason. He secretly sought dark magical powers with the plan of ruining Lee. He would eventually succeed.

When Lee was forty years old, his rival, named Wang (王 Wáng, "king"), put a curse on Lee. It was an ironic curse: he would be unable to die, either by disease, old age or violence, and never rest in peace. He would also gain knowledge of all things, but also suffer profound sadness and despair because of it. He would wander the world, forced to witness history in all its brutality.

Wang also murdered Lee's wife and children, and set it up so that Lee had committed the crime himself. Lee would be forced to flee China and wander in the Gobi for centuries. Not long after the incident, in 907, the Tang Dynasty fell and China was divided.

Sometime around the year 1200, a few years before Genghis Khan began to build his vast empire, Lee had a dream of a great ruler of a far away nation. It was Harun al-Rashid, the Abbasid caliph. He was told that he would need to go to Baghdad and settle there.

He would gain even greater wisdom through his studies at the House of Wisdom, living in a peaceful and prosperous city. That all ended in 1258, as Hulagu Khan and his forces destroyed the library and sacked the city. Before then, Lee, who had been following Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, became a Muslim and took the name Muhammad. He would fight, to no avail, in defense of his adopted home city.

(I chose the name because either Lee or Wang is the most common surname in the world, and Muhammad is the most common given name.)

After the conquest of Iraq, Lee fled to the city of Konya and Anatolia (now Turkey) and met a poet and mystic named Jalal al-Din Rumi. The two became friends and traveled together, once to Damascus, and Lee learned the teachings of Sufism. He believed that the Three Teachings he followed before, and the monotheistic faith of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, were all facets of the same truth, seeing all as one as God is one. He also learned, through another dream, that he would be allowed to rest in peace, but not until after the second coming of Christ, whom he would meet along with the Mahdi.

He remained with Rumi in the Mevlevi community until his death in 1273. Lee would continue his travels through Asia along the Silk Road. One day, in modern-day Kazakhstan, he met a man from Venice, another adventurer, named Marco Polo. They traveled together for a time, sharing what they learned. He also may have fought in the Crusades, though he hated war; he had witnessed enough already.

In the 14th century, he witnessed the rise of a new empire: that of the Seljuk Turks. A new empire, of the Ottomans, replaced the Seljuks, and in 1453, Constantiople was conquered. Lee would soon settle in the city now known as Istanbul.

In 1536, the Turks became allies with another great nation to the west: France. Lee would travel through Europe. He witnessed wars with other states, and the invasions of Vienna. He witnessed the rise of the West, and the revoltuions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

He learned of a young and distant nation: America. He was told in another dream that he was to go there. After traveling to India and Southeast Asia, he crossed the Pacific and settled in San Francisco in 1849. It was the beginning of the Gold Rush. He witnessed the greed and decadence associated with it. Meanwhile, he worked and lived among the laborers on the Transcontinental Railroad. (He was still physically forty years old.)

During his life in the United States, California became a state in 1850, the Civil War was fought and won by the Union, and vast industrial and technological advances were made.

He had renounced war, but would support the effort against the Japanese after learning what was done to Nanjing in 1937-38. After bearing decades of anti-Chinese discrimination, he finally became an American citizen soon in 1945, a few months after the end of World War II.

Also during his time in America, he fell in love for the first time after losing his wife over a thousand years before. They never married, however. He kept his curse a secret from all, including his beloved.

Though he would continue to work and travel throughout the world, it would be years before he would finally return to China in the early 21st century, when his company sent him to Beijing. He learned that his old rival Wang had also become immortal, and a very powerful wizard (a necromancer), who had planned on conquering China and the world. He was soon to face his enemy.

(Lee also wrote a diary, in many volumes, in his own language: a mixture of languages, mostly of Middle Chinese and Arabic.)

12 December 2014

What I do with my life

The only problem I have with this video is that it makes no mention of the maqam music of the Arab world, Turkey, the Caucasus, Central Asia etc. Nor does it mention Charles Ives and his quarter tone piano pieces. (Or my use of 72 equal temperament.)

But it does bring up Indonesian gamelan and Indian Carnatic music.

11 December 2014

Bonne anniversaire!

He, of course, is best known for his revolutionary Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14. (I chose to use French titles in most of the movements of my still-unfinished First Symphony in his honor.)

He also wrote an important work on orchestration (en français). I still need to study this, as well as Rimsky-Korsakov's.

09 December 2014

Japanese and "Sino-English"

Japanese itself, however, is not related to Chinese. Its family affiliation is unknown, and may be an isolate (unless the Okinawan languages are considered separate, then there would be a Japonic language family), but some linguists have argued it is related to Korean, and others claim both are Altaic, and thus distantly related to Mongolian and the Turkic languages. It does have a similar grammar to these, having a subject-object-verb word order, agglutinative typology with suffixes and possibly remnants of vowel harmony. However, genetic relation is established through regular sound correspondences in cognates, and few have been found, especially in comparison to Indo-European languages.

The words of Chinese origin, usually written using kanji, are called Sino-Japanese. Most kanji have two pronunciations, called 音読み on'yomi and 訓読み kun'yomi, meaning "sound reading" and "meaning reading" respectively. The on'yomi is the reading derived from Middle Chinese, but conforming to Japanese phonetics (tones are lost, as Japanese is non-tonal). The kun'yomi is the native Japanese word. An example is the word for "sword", 刀. In on'yomi, it is called tō, from MC *tau. In kun'yomi, it is the well-known name for the "sword", katana. In isolation, kun'yomi are generally used; in compounds, on'yomi, e.g. 日本刀 nihontō "Japanese sword".

(Korean too contains words of Chinese origin, but Chinese characters, called hanja in that language, are no longer commonly used. The phonetic hangul alphabet is generally used instead. Japanese uses two syllabries for phonetic writing when needed, called kana: hiragana for native words and suffixes; katakana for foreign words and onomatopoeia. Vietnamese, which too has many words of Chinese origin, once used Chinese characters, called chữ nôm, but now exclusively uses a Latin-based alphabet.)

Chinese words began to be inherited into Japanese because of the influence of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism on the island nation. (This also resulted in Shintoism, the originally shamanistic indigenous faith, becoming syncretic.) A similar phenomenon is the inclusion of Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek and Latin words in European languages, due to Christianity. However, English, Spanish, French, German and Russian do not use Hebrew or Greek letters to write Biblical words (though both Latin and Cyrillic are alphabets derived from Greek).

To get a better idea, imagine if many words, and word roots, used Chinese characters. For example, Chinese could be written "漢ese", and either pronounced "Chinese" or "Hanese". The word for "car" (automobile) in Japanese is 自動車 jidōsha (literally "self-moving cart"); in Sino-English, it could be pronounced "jidungcha" or "automobile" (or just "car").

And this leads to my idea of using Chinese characters with English (or any given language) as a "shorthand" in communications using a limited number of characters, such as Twitter with its 140-character limit.

This is actually related to the story of my planned Third Symphony, only it is about a Chinese person, whose native language is 9th century (Tang Dynasty) Middle Chinese, but after being cursed with immortality and forced to wander the world, his language gradually adopted words and even grammar from diverse languages until his return to China in the 21st century.

08 December 2014

Some notes on orchestration

Some points about individual instruments and groups:

- Flute: the lowest register should only be used when the orchestra is pian(issim)o. The middle and higher octaves get gradually louder and brighter. I like a combination of flute with trumpet (especially when muted) and oboe, with the flute(s) an octave higher than the others.

- Piccolo: the top note is usually listed as C, but I've written notes as high as D. A skilled player should be able to hit that high. In contrast, I like the notes of the often-ignored lowest octave, down to the low D (not many instruments reach C). They mix well with a solo flute in unison, but these should only be used when the rest of the orchestra is quiet.

- Alto/Bass flute: useful mostly in the lowest register, so again, should only be used in a very quiet environment. I use this when I want a "creepy" sound, like I do bass clarinet.

- Oboe: Even with the orchestra playing forte/fortissimo, this instrument can give some added edge to brass parts. It is not as delicate an instrument as it's often made out to be; its bright timbre can be quite penetrating. Unlike the flute, its sound is strong to the lowest notes. However, oboes (and double reeds in general) are the instruments I would least likely give quarter tones and other microtones (and I use these a lot, as you should know already).

- Oboe d'amore (in A): Will I ever use an oboe d'amore? Maybe I should just once...

- English horn (and bass oboe/heckelphone): like alto and bass flute, bass clarinet and contrabassoon, it's useful mostly for its low notes. It's use for pastoral-sounding or plaintive passages, best in a softer environment, is really cliché, so it should be used with more originality.

- Clarinet: It's really two instruments in one. The chalumeau register is ideal up to mezzo-forte. The clarion register really should be used as a kind of wooden trumpet. I like to beef up horn and trumpet parts in unison, maybe an octave higher. One should bear in mind the instrument's distinctive timbre--it's made up of odd-numbered harmonics. In atonal and highly chromatic music, I'd consider having the first clarinet in B flat and the second in A. This is also the best woodwind instrument for microtones, as the famous glissando in Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue shows. For these, the Albert (Simple) system, as used in Turkish, Balkan and klezmer bands, may be a better choice than Boehm or Oehler. (This would apply to open-holed instruments, not so much the plateau-keyed bass clarinet.)

- E-flat clarinet: often called a "small clarinet", this instrument has a sort of "wobbly" intontation and a bit of a mocking sound (c.f. the fifth movement of Berlioz' Symphonie Fantastique). I like to double piccolo parts an octave lower with it. Also, I like to use notes in the altissimo register, but these can sound strident and there can be intonation problems.

- Basset horn (in F), basset clarinet (in A): I wish these were used more often. We usually only hear the basset clarinet in performances of Mozart's Clarinet Concerto, K.622. Both these instruments have extensions to a written low C. Since these ultra-low notes use many ledger lines in treble clef, I may use a bass clef for these (basset horn sounding a fourth higher; basset clarinet a major sixth).

- Bass clarinet (and contrabass): Professional-level instruments have a low C extension, so I write parts down that low. Again, I may recommend bass clef for the lowest notes, and since modern instruments are always in B flat, they would sound a major second lower than written in bass clef. Though its distinctive sound comes through better when the orchestra is playing less loudly, it can beef up the sound of the bassoons and trombones/tuba. I like to combine it with contrabasson an octave or a fifth higher. (In the latter case, I use parallel fifths in the same way a "resultant" stop would be used on organ, or a power fifth on guitar in rock.)

- Bassoon: As Stravinsky proved to us all (with difficulty at first), the altissimo register can sound impressive. I may never really need a bass oboe or heckelphone in that case. As for the lower notes, this is where the instrument is strongest. I have bassoons playing in unison with trombones and/or tubas all the time for a nice timbral blend, like I have oboes add brightness to trumpets or horns. One more thing: I rarely use tenor clef. I prefer to use treble clef an octave lower. (C clefs are for violas, if you want my honest opinion.)

- Contrabasson: the lowest-pitched of all the commonly-used woodwinds. (If only there were such a thing as a "triple bassoon", a subcontra.) But I don't just use it for the first octave. It has a distinctive sound, a little like a baritone saxophone, in its middle range, and I like to exploit that. I probably wouldn't use notes above the high G though.

- Saxophones: the last-chair oboe and bassoon I'll usually have doubling alto/soprano and tenor saxes, respectively. Baritone or bass sax, and contrabass sarrusophone, may be used in lieu of contrabassoon. I combine alto and tenor saxes with strings in one of the movements of my Symphony No. 2 for a romantic sound (got that idea from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet)

- Horn: one of the most challenging instruments of all to play. And I like to challenge performers. I use horns in melodic passages far more than I do trumpet or trombone; I tend to emphasize the harmonic series more for the latter two. Because intonation and timbre is governed so much by the position of the hand within the bell, I write quarter tones and other microtones for horns very frequently. I also tend to use higher notes (since I assume double horns, F plus high B flat, are being used), as high as the D above the staff or so. As for the low pedal notes, I try not to overuse these, but I may use the fourth horn as a "second tuba" on occasion.

- Trumpet: I use B flat trumpets unless otherwise specified. The seventh harmonic, usually ignored, is going to be used frequently by me. I treat these as a B two-thirds tone flat or A third-tone sharp, which I write as B flat with arrow down or A sharp with arrow down. The eleventh harmonic is treated as a fourth a quarter tone sharp or a tritone a quarter tone flat (so backwards flats and single-vertical sharps are used). The highest harmonic I will likely use for trumpets and trombones is the twelfth, a high G above the staff for trumpet. Also, I may be using the third valve slide as a microtuning device.

- Trombone: As a matter of habit, I use two tenors and a bass (or maybe an alto, tenor and bass). The bass trombone may use a few pedal tones sometimes, doubling the tuba in unison as well as an octave or fifth higher (again, making power chords in the latter case). Naturally, trombones, like the violin family, are perfect microtonal instruments, but with limited technical speed.

- Tuba: I assume an E flat / low B flat four-valve bass tuba by default. Pedal tones, possibly well into the zeroth octave, may have to be played. I always use bass clef, non-transposing.

- Timpani: Four to six, one or two players. For a full set, and in a tonal/modal/maqamic situation, I like to tune them to a pentatonic scale in an octave range. For atonal pieces, things may get weird.

- Piano: I recommend using a Bösendorfer Imperial if possible, for the low C extension. (I know they're expensive.) Also, a second upright piano tuned a quarter tone (50 cents) flat should be placed nearby. I got the idea from Charles Ives, naturally. And one more thing: a piano also doubles as a percussion instrument. I got that idea from Edgard Varèse.

- Harp: I usually only use one, but two will obviously be needed if I need a full chromatic scale. (I don't like using any more instruments than is necessary.)

- Strings: the usual five-part ensemble. Since I'll often have the parts divisi, as I do the winds, that means as many as ten string parts (actually, probably only nine, since I may never divide the basses). Cellos and basses will often play power fifths. Obviously, these fretless instruments will be covering the lion's share of microtonal notes.

01 December 2014

The world sucks. That's why it needs us.

I've been talking about this a lot. I've become a lot more pessimistic lately. Among the great philosophers, you won't find any greater pessimist than Schopenhauer.

It turns out he had a lot of say about aesthetics(see also here). His writings on the arts were read by Wagner, He was also an influence on Nietzsche, who once said that without music, life would be a mistake.

To summarize the points Schopenhauer made, and I make:

- Life is a prison of suffering. It is so because of will: urges, desires, passions. We always want something. We want too much. We want what we cannot or should not have. Wealth, power, pleasure, it's never enough. And it's all irrational. There are things better for us, and better, but they don't attract us.

- Life is also full of illusion and delusion. It's all a big lie. Nothing is ever as it seems. People and things get judged too much by their outward appearances. We're always deceiving ourselves about something. Those we love and trust betray us. We get sick and our bodies and minds betray us. The world, which we hope will have good things for us, betrays us. Our faith and hope betrays us. Our perceptions definitely betray us.

- Yet we choose to live, most of us. We don't want to die. So what makes life bearable? Beauty. Art. Sometime from beyond this world. And among the forms of art, music is the highest, since it is the most abstract. It is an idea in its purest form, the most mathematical.

16 November 2014

Doing it my way

16 September 2014

Symphony No. 2, again

About that symphony again... it's really a huge suite of preludes for orchestra, 52 in all. Each one is inspired by something interesting about each of the 50 US States, plus the District of Columbia and the territory of Puerto Rico. It could be a natural landmark, a man-made structure, an historical figure or event, or in the case of Maryland, the state flag. Classical forms may be used, such as a fugue (Pennsylvania) or sonata form with repeat (Louisiana, but recapitulation is in Missouri). A number of featured solo instruments will be used; the middle 11 movements (Louisiana through Minnesota) would be like a piano concerto.

The main inspiration for the work is Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, as orchestrated by Ravel. Like that work, with the Promenade, there are recurring themes, the first presented as a hymn-type piece in the first movement, Maine. It opens with the three "Masonic chords" heard in the Magic Flute. The overall key is E flat major, but all 24 major and minor keys will be used, along with a number of atonal movements and several Arabic maqam scales using quarter tones.

I've finished, or almost finished, about 13 of the movements. They vary in length from less than two minutes for D.C. (a simple fanfare) to around ten minutes for the yet-unwritten Texas movement (a violent scherzo in D minor, à la Night on the Bare Mountain). The total length of the work should be around three hours.

05 August 2014

What a dying composer sounds like

04 August 2014

My new classical-album-soundtrack routine

- a long-form classical composition (symphony, symphonic suite, concerto, opera, ballet), usually for full orchestra, but it could be a chamber (e.g. string quartet) or solo work (e.g. piano sonata)

- an entire non-classical album, usually jazz, progressive rock/metal or world music

- a soundtrack of a film, TV show or video game

The Boy Who Named Himself (a short story)

One of the earliest events of the DIES IRÆ story (of Symphony No. 1) is that of Hris (written حريس in the Kitâb al-Majnûn, a mysterious and long-lost book written in Baghdad around 1250--more on that in a future blog post), a young orphaned warrior who became a philosopher and scientist, possibly the first ever.

He had forgotten the name given to him at birth, so he called himself Hris (in the modern Elven language: Ħrì, with a falling tone), meaning "the free one" in his prehistoric language (which may have been Nostratic). He lived in the Levant around the year 13000 BC. He was a young warrior, thirteen years old, the sole survivor of a tribe that was wiped out in war. He managed to flee to a distant land and dwelt in caves for three years. During his time in seclusion, he first remembered having to kill a man in battle, and chose to forever forswear violence, even towards animals, except in self-defense, as he subsisted from only gathered fruits and vegetables, mushrooms, wild honey and the milk of animals he had adopted as pets.

Having little to do other than contemplate the world, he developed his philosophy further: soon after, he came to reject the gods (that is, dead warriors, chiefs and other heroes that had been deified) of men, and serve only nature and truth, wherever it may be found. He would spend his lonely days observing and learning from nature.

At age 16, a girl was gathering berries near where Hris lived. They met, fell in love and chose to live together for life. He told her early in the relationship, "You are my equals; I must respect you as I did my mother and sister." From there, he denounced the idea that any person could own and treat any other as property. He saw all men and women as equals, and swore to oppose the tyranny and injustice too often seen in leaders. They had a number of sons and daughters, and they taught them their enlightened ways.

Sadly, Hris would meet a tragic end at the hands of a group of warriors he had tried to preach to. They captured him and his family. He was tortured and killed, but his wife and children escaped. She took the name Hrith, the feminine form of Hris, and her family returned to her husband's homeland and establish a powerful nation there. Their descendants would build a great city, which thrived from trade and peaceful relations with neighbors, until it suddenly collapsed from within around 9600 BC.

Among the things Hris is said to have invented, according to the legends: monotheism (though some would say atheism), agriculture, astronomy, writing, mathematics, music, poetry, several musical instruments and early forms of medicine, the scientific method and democracy. It is claimed that he built a harp or lyre from the bones and other remains of a son that had tragically died in childhood; he was himself a music lover, and his father believed this is how he could "live forever".

03 August 2014

Intervals (of 31-tone) ranked by consonance/dissonance

I wanted to do my own ranking of all the degrees of the 31 pitch classes of my tuning system (by using 31 equal temperament, which is an extended meantone system that contains quarter tone-type intervals and approximates 11-limit just intonation well). However, I'm working with an irrational temperament rather than just ratios, and I want to use a more scientific understanding of consonance and dissonance than merely looking at numerators and denominators.

This is where Boston-based guitarist and music theorist Paul Erlich comes in. He came up with the idea of harmonic entropy (see also this). (Of course Boston has its own established microtonal music scene.)

Using the Scala tuning program, I calculated the entropies (dissonances) of the pitches of 31 equal. In order from lowest to highest (not counting the unison):

- 31. perfect octave

- 18. perfect fifth

- 1. semi-augmented prime / diesis ("quarter tone")

- 13. perfect fourth

- 23. major sixth

- 10. major third

- 8. minor third

- 30. semi-diminished octave

- 25. augmented sixth (~ 7th harmonic)

- 15. augmented fourth

- 21. minor sixth

- 26. minor seventh

- 7. augmented second (~ 7/6 minor third)

- 5. major second

- 27. neutral seventh

- 6. semi-augmented second

- 12. semi-diminished fourth

- 16. diminished fifth

- 19. semi-augmented fifth

- 11. diminished fourth

- 9. neutral third

- 28. major seventh

- 22. neutral sixth

- 14. semi-augmented fourth (~ 11th harmonic)

- 20. augmented fifth

- 4. neutral second

- 24. diminished seventh

- 17. semi-diminished fifth

- 3. minor second / diatonic semitone

- 29. diminished octave

- 2. augmented prime / chromatic semitone

01 August 2014

My "Pathétique theory": composers' favorite "drama keys"

- Bach: D minor, for his famous Toccata and Fugue and a few of his concerti.

- Mozart: G minor, his 25th and 40th Symphonies, influenced by the Sturm und Drang movement in early German Romanticism.

- Beethoven: C minor. His 8th "Pathétique" and 32nd Piano Sonatas, Symphony No. 5.

- Chopin: I'm guessing C sharp minor? (Anyway, piano composers tend to like keys with more sharps or flats; they're easier to play.)

- Tchaikovsky: B minor, for Romeo and Juliet (not the D flat major love theme, obviously), that famous part of Swan Lake, his last Symphony, also nicknamed "Pathétique".

28 July 2014

When we talk about "classical music"...

You can also teach yourself most of what you'd learn at a university just by reading Wikipedia articles. (But I'd always study further elsewhere.)

There isn't really a set definition of what is collectively called "classical music", so I try to avoid using the term except when talking about Classical-era music (Haydn, Mozart, earlier Beethoven), and use "Western common practice" as a broad term to include the the Baroque, Classical and Romantic eras. (This does not include early music, i.e. the ancient, medieval, or Renaissance eras; nor does it include modern-contemporary music. However, the lines that begin and end common practice are blurry; one has to set an arbitrary date range, such as 1600-1900.)

What unites common practice music? A number of things:

- a chromatic scale with twelve notes per octave; the gradual dominance of equal temperament; quarter tones and other microtonal intervals were never used

- tonality based on major and minor keys, with major and minor scales (for the latter: natural, harmonic and melodic), as opposed to modes in early music and atonality in much modern music

- relatively little distinction between sacred and secular music

- functional harmony, predictable chord progressions and cadences

- divisive meters (simple and compound), rather than additive meters, and a steady pulse and a generally consistent tempo (the usual time signatures were 4/4 or common time, 2/4, 2/2 or cut time / alla breve, 3/4, 6/8, 9/8 and 12/8, with little use of odd meters such as 5/4 and 7/8)

- the virtual disappearance of notes longer than a whole note (i.e. breve, longa, larga); the end of mensural notation and the dominance of modern staff notation

- the establishment of bel canto and the standard tessituras of soprano, alto, tenor and bass voices

- the widest gulf between "high" (art) and "low" (popular and folk) musics; this would begin to be broken down in the modern era

... and so on and so forth.

27 July 2014

Quarter-, third- and sixth-tone accidentals

The sixth-tone sharps and flats (the natural signs with arrows) are also used when a third-tone accidental is combined with a regular one, e.g. third-tone sharp plus (half-tone) flat equals sixth-tone flat.

These symbols are contained in fonts available in Finale and Notepad, and also Sibelius and the Scorch reader.

22 July 2014

The Istanbul Manifesto (work in progress)

While having a great deal of diversity, we would be united by these concepts:

- The innovations and revolutionary ideas of the 20th and early 21st century masters would be continued, with serialism, minimalism et cetera being used not as genres unto themselves as much as techniques. At the same time, the music would be rooted in the music of the common practice era (Baroque, Classical, Romantic) as well as early-music era, while still progressive in outlook. (It would take Liszt and Wagner's side in the "War of the Romantics".)

- In the spirit of the ancient city which straddles the natural border between Europe and the Middle East (the Bosphorus), non-Western musical styles will be explored, with their melodic complexity that often uses pitches outside the conventional twelve-tone scale, and complex rhythms in both additive and divisive meters. Also, it would be important to treat these "world music" styles with respect and not misrepresent them as Ersatz. Appreciate, don't appropriate.

- For reasons stated above, and in the spirit of experimentalism/the avant-garde, tuning systems not based on the twelve-tone equal tempered scale should be greatly employed. I personally will be using 72 equal divisions of the octave, but other tunings--19, 22, 31, 41, 53 and other equal temperaments, Harry Partch's 43-tone just scale, historical meantones and well-temperaments--should also be explored.

- These ideas should be implemented not only in "high" art music, but in popular styles in a spirit of populism, while not "selling out" or "dumbing down". Progressive rock and metal in particular is fertile ground for such ideas. Another related concept is Gebrauchsmusik, that music should often have a useful purpose (including in theater, film, video games and the like), though it should always stand on its own merits.

- The relationship between music and other arts, and also literature and philosophy, should also be emphasized, as these disciplines are ultimately inseparable. Again, the emphasis will be on modern and postmodern schools of thought.

More ideas to be added as they come to me.

17 July 2014

Taking a break from composing; studying instead...

I'm also looking for anything about his grandson, Georgy Rimsky-Korsakov (article from German Wikipedia), himself a St. Petersburg-based composer who wrote quarter-tone pieces.

13 July 2014

Apollo vs. Dionysus in an eternal football match

I was writing all kinds of positive and negative canons and weird inverted this and retrograde that and getting as spaced-out mathematically as I could and I was going "Wait a minute (laughs), who cares about that stuff?" I had always liked rhythm and blues so here I was stuck between the slide rule and the gut bucket somewhere and I decided that I would opt for a third road someplace in between.--Frank Zappa, interview with Martin Perlich, 1972

There's a concept in philosophy: a dichotomy between the Apollonian aspects of art (intellectual, logical, "left-brained") and the Dionysian (emotional, "right-brained"). Nietzsche (with whom I've always had a love-hate relationship) is famous for developing this theory in The Birth of Tragedy, though he was not the first in doing so, even among modern German philosophers.

I'm oversimplifying a bit, but art music (i.e. classical traditions from around world; also jazz) tends to be Apollonian; popular and folk music Dionysian. My goal is to make my music a balance of both, intellectual and emotional.

The intellectual aspects come from many sources, from Baroque fugues and other counterpoint, to Classical form, to Modernist serialism and mathematical experimentation. The emotional from Romanticism, music from film, television and video games, and of course, popular music forms. Beethoven and Stravinsky both sought a balance of Apollonianism and Dionysianism, the latter in his later Neoclassicism and his earlier primitivism of The Rite of Spring.

My use of microtonality is also linked to this opposition. I arrived at 72 equal divisions of the octave after doing some middle-level mathematical calculations, finding a convenient equal temperament that approximates just intonation best, beyond the imperfection of 12-tone tuning. I also wanted to "paint with more colors", expressing moods well beyond the major and minor dichotomy.

I'm also taking a balanced populist approach to composing, writing for a broad audience and avoiding too much elitism while not dumbing myself down. I do the same for philosophy and other sciences.

Edit: I use the website TV Tropes a lot when talking about philosophy. There is an article on Enlightnment (in music, the Baroque and Classical eras) versus Romanticism.

06 July 2014

A quote about Béla Bartók, from a book I've been reading

"Like Grainger in England, Bartók brought with him an Edison cylinder, and he listened as the machine listened. He observed the flexible tempo of sung phrases, how they would accelerate in ornamental passages and taper off at the end. He saw how phrases were seldom symmetrical in shape, how a beat or two might be added or subtracted. He savored 'bent' notes--shadings above or below the given note--and 'wrong' notes that added flavor and bite. He understood how decorative figures could evolve into fresh themes, how common rhythms tied disparate themes together, how songs moved in circles instead of going from point A to point B. Yet he also realized that folk musicians could play in absolutely strict tempo when the occasion demanded it. He came to understand rural music as a kind of archaic avant-garde, through which he could defy all banality and convention."--Alex Ross, The Rest is Noise, p. 83

30 June 2014

Ideas for novels, screenplays, video games and the Symphonies

- A devout Catholic loses his job, his family, his home and his health through no fault of his own (and partly though the malice of others). Feeling abandoned and betrayed by God, he plots to kidnap and murder the Pope to get God's attention. (Obviously a philosophical story, something Dostoevskian.)

- A young metal bass player/vocalist in Texas just had yet another band break up, and his musical career seems a failure. He leaves Austin and returns to his small East Texas hometown, and begins to dabble in contemporary classical. He befriends a composer in Turkey, and falls in love with a Russian pianist who's become a YouTube celebrity. He ends up being invited to Istanbul to stay with his friend, who unbeknownst to him has also invited the pianist. The next two weeks will be the adventure of his life. (Music from Symphony No. 2 may be used.)

- A sociopath is terrorizing New Orleans, kidnapping young women and men, locking them in a secret dungeon, and raping, torturing and killing them ritualistically, as human sacrifices, while playing a recording of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring. A veteran police investigator is assigned the case, with only the maimed corpses of victims as evidence.

- (Part of the plot to my Symphony No. 1.) In modern-day Lebanon in the year 9600 BC, a civilization is in ruins, destroyed by hostile neighbors and betrayal from within. The story is how a people, the Hria (meaning "[the] free, noble [people]" in the ancient Hrith language--حريا in Arabic script), evolve from hunter-gatherer level through agriculture and pastoralism, form a city-state, develop technology rivaling that of modern industrialized nations, then quickly falls under tyranny and collapses. The only evidence of their existence is in mystical writings randomly appearing through different times and places, particularly in a book written in Baghdad shortly before being sacked by the Mongols in 1258, and another found in Saint Petersburg, allegedly by Rasputin near the end of his life.

- (The plot to Symphony No. 3, which I've only just begun to start writing). The most common surname in the world is 李 Lǐ, often written "Lee" in English. The most popular given name is Muhammad, from Arabic. So I created an "everyman"-type character named Muhammad Lee, who would naturally be a Chinese Muslim. This character was born during in Xi'an (formerly Chang'an) during the Tang Dynasty, around AD 900. Lee was of noble birth and noble character, but was betrayed by a rival who cursed him with immortality. Lee would spend the centuries wandering the earth--to Baghdad, Venice, San Francisco, Beijing in the future--witnessing and documenting historical events. He was to only rest in peace after the Second Coming.

19 June 2014

The beginning of an autobiography, or "musical manifesto"

There was music playing in the house non-stop. Beethoven, Beatles, Bacharach, Bee Gees... you name it. That's how I was able to learn tunes by ear, and gain the (supposedly) rare gift of perfect pitch. I've had a lot of practice. I lucked out in life.

I was discovered John Williams and his film scores for Jaws and Star Wars--but the composition that had the greatest impact on my life: Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring, which we know caused a riot upon its 1913 Paris premiere.

In future years, I picked up other instruments: guitar, bass, clarinet, saxophone, flute--but bass and piano are my favorite two. (I'm a lot better on bass; I've always naturally gravitated toward low pitches.)

I'm amazed I didn't become a serious composer until much later. I played bass in bands (that never went anywhere), and wrote a few piano pieces here and there (most lost), but I never felt like I could be anything but an imitator. I needed to find my own voice.

I had also been a music major at the university in my East Texas hometown, but only attended for about a year before dropping out due to mental health-related issues. Much of what I know I've taught myself, especially concerning modern and postmodern musical trends.

The "gimmick"

I had heard quarter-tone music before, mostly the work of Charles Ives (such as his three Quarter-Tone Pieces), but until I began to embrace modernist music, I didn't take it seriously. I entered the world of microtonality (or xenharmonia) via a more traditional route: Middle Eastern music.

It turns out that the Arabs, Turks and Iranians have been using quarter tones and even smaller intervals for many centuries, and literally hundreds of scales and modes called maqams. I listened to various popular songs, either as MIDI arrangements or downloaded via P2P (Napster et al), to acclimate myself to this exotic 24-tone scale.

Around the same time, I discovered another American composer: Harry Partch, remembered for using a 43-tone just intonation scale. I started listening to his music and bought his book, Genesis of a Music, and studied it (I still have yet to read all of it).

But it took me a long time to decide which tuning system I wanted to use myself. Eventually, I settled on 72 equal temperament. Not only is a multiple of twelve (dividing the equal-temperament semitone into six equal parts), but it very precisely approximates 11-limit just intonation, which Partch advocated. I started making experimental MIDI files using pitch bend messages at points when appropriate.

Eventually, in 2008, I wrote my first full 72-tone composition: "The Waterloo Rag", a type of stride/novelty/blues/boogie-woogie piece for six player pianos, each tuned 16 2/3 cents apart in a range of -50 to +33 1/3 cents from A=440 Hz tuning. (Waterloo is the former name of Austin, Texas, where I've been living for over a decade.)

I also have had an agenda. While composers like Chopin, Liszt, Dvořák, Sibelius, Copland and the Russian Five sought to promote a nationalistic musical style for their nations, my goal is musical internationalism and eclecticism--a marriage of Eastern and Western styles, forms and techniques (including tunings), past and present, art music and popular and traditional music.

American Mahler

The first one, if I ever finish it, may be four to six hours long. (Mahler's Third, the longest among works of the common repertoire, is a relatively brief 90 minutes; Havergal Brian's Symphony No. 1, the "Gothic", the world record holder overall, is around two hours.) The theme of my First: the Apocalypse more or less. It's a story I've been developing in my head since around the time I started making up the music.

The second would be a more merciful two hours in length approximately, with fifty-two movements: one for each US State plus the District of Columbia and the territory of Puerto Rico (with a larger population than 22 States). Its main inspiration is Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, and like the "Promenade" in the Russian composer's magnum opus, there is a main theme introduced in the first movement, "Maine: Light, Hope". (Another inspiration is the Beach Boys' SMiLE project, itself intended to be a musical trip across America, with eclectic influences.) The grand finale will be titled "California: The Great Gate of San Francisco". All twenty-four major and minor keys are to be used along with atonal movements, and various non-conventional instruments will be used, including banjo, accordion and Benjamin Franklin's glass armonica.

There are also plans for a third and fourth symphony in the more distant future, but I need to work on the first two first. (I have to write things non-linearly, as inspiration comes to me. I can go through long bouts of writer's block.)

The other thing I'm doing currently is familiarizing myself more with the music of India (Hindustani/North and Carnatic/South), as I've studied Middle Eastern music so extensively.

I also may finally finish school someday. I'm really wanting to go to Berklee College of Music in Boston, where there's a nice microtonal scene that also specializes in 72-tone. Still, I probably write more music in conventional twelve-tone, and I do use serialism as a technique (and microtonal rows) on occasion.

13 June 2014

Partch Plus in my 72edo notation (rough draft)

- 1/1 (0) G (392 Hz)

- 81/80 (1) G↑

- 64/63* (2) G‡↓

- 33/32 (3) G‡

- 28/27* (4) G‡↑

- 21/20 (5) G#↓

- 16/15 (7) Ab↑

- 12/11 (9) Ad

- 11/10 (10) Ad↑

- 10/9 (11) A↓

- 9/8 (12) A

- 8/7 (14) A‡↓

- 7/6 (16) A‡↑

- 32/27 (18) Bb

- 6/5 (19) Bb↑

- 11/9 (21) Bd

- 5/4 (23) B↓

- 14/11 (25) B↑

- 9/7 (26) Cd↓

- 21/16 (28) Cd↑

- 4/3 (30) C

- 27/20 (31) C↑

- 15/11* (32) C‡↓

- 11/8 (33) C‡

- 7/5 (35) C#↓

- 10/7 (37) Db↑

- 16/11 (39) Dd

- 22/15* (40) Dd↑

- 40/27 (41) D↓

- 3/2 (42) D

- 32/21 (44) D‡↓

- 14/9 (46) D‡↑

- 11/7 (47) D#↓

- 8/5 (49) Eb↑

- 18/11 (51) Ed

- 5/3 (53) E↓

- 27/16 (54) E

- 12/7 (56) Fd↓

- 7/4 (58) Fd↑

- 16/9 (60) F

- 9/5 (61) F↑

- 20/11 (62) F‡↓

- 11/6 (63) F‡

- 15/8 (65) F#↓

- 40/21 (67) Gb↑

- 27/14* (68) Gd↓

- 64/33 (69) Gd

- 63/32* (70) Gd↑

- 160/81 (71) G↓

- 2/1 (72) G

11 March 2014

Symphony No. 2, or, A 19th Century Russian Composer in 21st Century America

Mussorgsky himself was inspired to write “Pictures” when his friend, artist Victor Hartmann, died suddenly. He imagined his sketches as part of an exhibit: a ten-movement work, each preceded by a leitmotif he called “Promenade”. I’m doing something similar for my Symphony, only with fifty-two movements, for the fifty American States plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, each individual piece inspired by photographs from each state.

While Mussorgsky imagined a trip to a museum, I chose to subtitle my opus “Great American Road Trip”. (The movements for Puerto Rico, Alaska and Hawai’i would require a different means of transportation, of course.) I’m expecting the finished work to be over two hours long, most movements taking up two to three minutes each, but a few as much as five.

Some features of the work:

- Since each movement could be considered a “prelude” of sorts, I’m using all twenty-four major and minor keys, with the remainder of the movements repeating a key, or being atonal. At least one of the movements will use a tonality based on a quarter tone, or an Arabic maqam (including a taqsim on Maqam Bastanigar for clarinet in the Michigan movement). Since the key is constantly changing, this would almost be an example of the progressive tonality of Mahler’s symphonies, except the first and final movements will both be in E flat major, the overall key of the work.

- Soloists will be featured at various times. For the middle movements, this will be piano, so the work will sound a bit like a piano concerto. Other instruments to be used: harpsichord, guitar, banjo, accordion, Latin percussion and church organ.

- Various popular styles will be used, such as bluegrass for Kentucky and Tennessee, jazz for Louisiana and Missouri, polka and Irish reel for Illinois, tejano for Texas.

- The fifty-two movements are organized into five parts:

Part One (1-12): Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, District of Columbia.

Part Two (13-22): Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Puerto Rico.

Part Three (23-33): Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota.

Part Four (34-42): North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas.

Part Five (43-52): New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, Hawaii, California. - For the Nevada movement, I want to use Harry Partch’s 43-microtone scale, but probably approximated in 72 equal temperament for convenience.

To get you started, here’s the first movement, Maine.

06 March 2014

Instead of cents, why not degrees?

Alternative scale measurements propose include the SI/metric-inspired millioctave (the thousandth root of two), the savart (which uses base-10 logarithms instead of base-2), and my preferred measurement: the arc degree. Here, I think of the octave (the 2:1 ratio of frequencies) as a circle, with each note of the scale repeating for each octave, and one degree being 1/360 of an octave, 3 1/3 cents each. For finer measurements, minutes and seconds could be used, or merely degrees with decimal fractions.

But why divide the octave into 360 degrees? Answer: 360 is a multiple of 72, and 72 equal temperament is an excellent ET approximation of just intonation, especially 11-limit, that just happens to be a multiple of twelve. It is also a multiple of twenty-four, as used in modern Arabic quarter-tone tuning, and thirty-six, used in some Iranian systems. Also, the ET whole tone is divided into sixty equal parts, and sixty is the smallest natural number divisible by all integers from one through six.

Some measurements in degrees:

- octave (2/1): 360°

- equal whole tone: 60°

- equal semitone: 30°

- equal quarter tone: 15°

- just perfect fifth (3/2): 210° 35′ 11″ or 210.59° (12et 210°)

- just perfect fourth (4/3): 124° 24′ 49″ or 149.41° (12et 150°)

- just major third (5/4): 115° 53′ 39″ or 115.89° (12et 120°, 72et 115°)

- just minor third (6/5): 94° 41′ 33″ or 94.69° (12et 90°, 72et 95°)

- just blues minor third (7/6): 80° 3′ 41″ or 80.06° (72et 80°)

05 March 2014

An official name for “Language P”

The first word is of Arabic origin: دنيا, borrowed into Hindustani, Bengali and Malay. The second is from Latin via Spanish and Portuguese, meaning “language” and “tongue”, with cognates in English and French.

Also, it will also be based on the twelve most spoken languages, L1 and L2 combined, according to Ethnologue, weighted accordingly:

- Chinese (Mandarin) 9

- English 7

- Hindi-Urdu 4

- Spanish 4

- Arabic 4

- Russian 3

- Portuguese 2

- Bengali 2

- Malay-Indonesian 2

- Japanese 1

- French 1

- German 1

08 February 2014

Symphony No. 2 in E flat major (work in progress)

The Second Symphony is to have fifty-two movements—one for each American State plus the District of Columbia, where the national capital Washington is located, and Puerto Rico, the largest of the Territories, which could someday be State. These movements would be inspired in some way by each state, ordered geographically and grouped into five parts:

- Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, District of Columbia (1-12)

- Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Puerto Rico (13-22)

- Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota (23-33)

- North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas (34-42)

- New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, Hawaii, California (43-52)

Unlike the Brian’s or Mahler’s Eighth, the instrumentation of my Second is going to be a lot simpler, more Classical-to-early Romantic, at least for now. Some of the features of a Baroque concerto grosso will be used, with the ripieno as such:

- two flutes, second (or both?) doubling piccolo

- two oboes, second doubling cor anglais

- two clarinets in Bb or A, second doubling bass clarinet

- two bassoons, second doubling contrabassoon

- four horns in F

- two trumpets in Bb

- three trombones, two tenor and one bass, the last doubling tuba

- three or four timpani plus other percussion including Latin

- one harp

- twelve first violins

- ten second violins

- eight violas

- six violoncellos

- four contrabasses

Number of strings may vary.

Inspiration comes from all my favorite symphonies and symphonic suites, particularly late Romantic and early Modern, but with Baroque counterpoint, Classical forms and Modern atonality, serialism and microtonality. At tiimes, jazz and pregressive rock influences could be heard.

I’ve already started on the project; some of it can be heard at SoundCloud. Be sure to check back for updates both to this blog entry and the music.